Ambedkar on Savarkar is a fiery topic—a clash of visions for India’s soul. Did they meet? What did Ambedkar say? Did they share a bond or battle?

Let’s dive into what Ambedkar said about Savarkar, their Ambedkar letter to Savarkar, and whether Ambedkar met Savarkar, unpacking a debate that still sparks on X.

Ambedkar on Savarkar: A Dialogue on Reform,

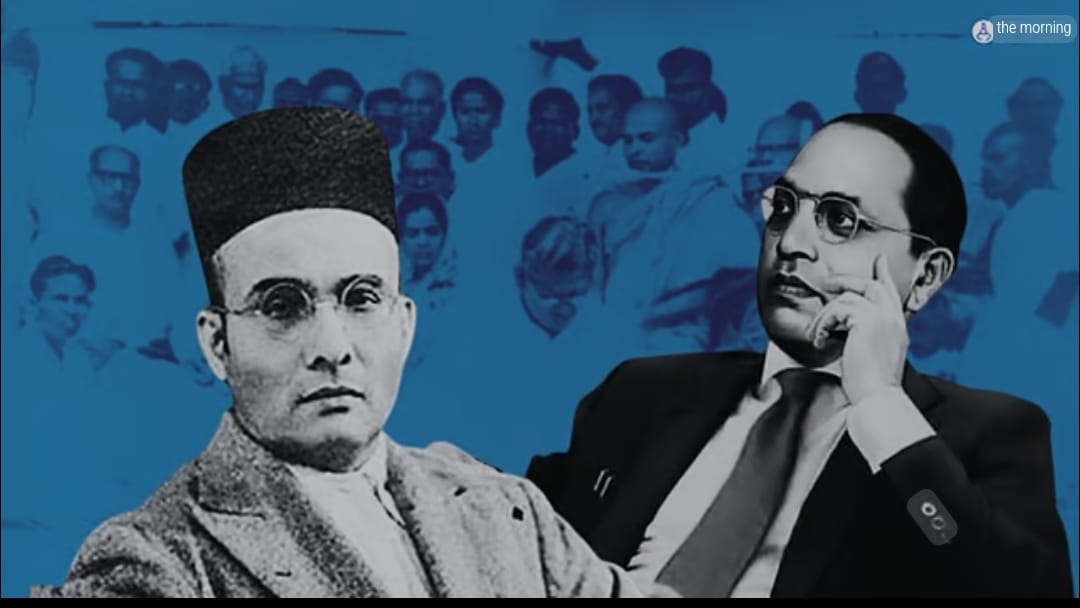

The relationship between Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and Vinayak Damodar Savarkar is a fascinating chapter in the story of modern India. Both men were towering figures-Ambedkar as the chief architect of the Indian Constitution and champion of Dalit rights, and Savarkar as the originator of Hindutva and a prominent social reformer. Yet, their visions for India, especially on caste and religion, often stood in contrast. Let’s explore their interactions, differences, and the legacy of their engagement.

Two Reformers, Two Paths

Ambedkar and Savarkar both recognized the deep injustices of the caste system and untouchability. Savarkar, particularly during his years in Ratnagiri (1924–1937), was active in anti-caste campaigns- organizing temple entry movements, promoting intercaste dining, and even opening a pan-Hindu café where all castes, including “untouchables,” could eat together. He believed that for India to be strong, Hindus needed to unite, which meant abolishing untouchability and, to some extent, caste barriers.

Ambedkar, meanwhile, was leading mass movements for Dalit rights, such as the Mahad Satyagraha and the Nashik temple entry campaign. But while Savarkar sought to reform Hinduism from within, Ambedkar became increasingly convinced that the system was beyond repair. His eventual conversion to Buddhism in 1956 was a powerful rejection of Hindu orthodoxy and caste hierarchy.

Ambedkar’s Letter to Savarkar

One of the most telling episodes in their relationship is Ambedkar’s letter to Savarkar. In 1933, when Savarkar opened a temple in Ratnagiri for all Hindus, including Dalits, he invited Ambedkar. Ambedkar couldn’t attend due to prior commitments but wrote to Savarkar:

“I, however, wish to take this opportunity of conveying to you my appreciation of the work you are doing in the field of social reform. If the Untouchables are to be part of the Hindu society, then it is not enough to remove untouchability; for that matter you should destroy ‘Chaturvarna’. I am glad that you are one of the very few leaders who have realised this.

Ambedkar praised Savarkar’s efforts but also criticized his continued use of the concept of chaturvarna (the four-fold varna system), urging him to abandon it altogether. This exchange shows mutual respect for each other’s reformist zeal, but also highlights their philosophical divide.

Did Ambedkar Meet Savarkar?

While Ambedkar expressed a desire to meet Savarkar, there is no definitive record of a formal meeting between the two leaders. Their correspondence, however, reflects an intellectual engagement and acknowledgment of each other’s work.

What Did Ambedkar Say About Savarkar?

Ambedkar’s comments on Savarkar were nuanced. He appreciated Savarkar’s social reform initiatives but was critical of the limitations of Savarkar’s approach. Ambedkar believed that simply removing untouchability was insufficient; the entire caste system, including the ideology of varna, needed to be dismantled. He saw Savarkar’s vision of pan-Hindu unity as ultimately constrained by its inability to fully break with caste hierarchy.

Ambedkar’s own path led him to denounce Hinduism as inherently unequal, culminating in his conversion to Buddhism moved Savarkar publicly to criticize as “useless,” to which Ambedkar retorted by questioning the value of Hindu unity if it could not deliver justice to the oppressed.

Case Study: Social Reform in Ratnagiri

Both leaders were active in Maharashtra, particularly in Ratnagiri. Savarkar’s anti-caste campaigns sometimes overlapped with Ambedkar’s movements, leading to both cooperation and competition. British officials at the time noted that Savarkar’s activism could “interfere with the work of Ambedkar in the region,” reflecting the complex dynamics between their movements.

Legacy and Contrasts

Ambedkar and Savarkar shared a commitment to social reform but differed fundamentally in their methods and ultimate goals:

- Savarkar sought to modernize and unify Hindu society by eradicating untouchability, but within a Hindu nationalist framework.

- Ambedkar aimed for a radical transformation, rejecting Hinduism itself as irredeemably tied to caste, and advocating for a new, egalitarian social order.

Their legacies continue to shape debates about caste, religion, and national identity in India. Ambedkar’s inclusive vision, rooted in constitutional equality, stands in contrast to Savarkar’s Hindu-centric nationalism, which critics argue can be divisive.

Summary

The dialogue-sometimes direct, often indirect-between Ambedkar and Savarkar is a testament to the richness and complexity of India’s social reform movements. Both men challenged orthodoxy and inspired millions, but their visions for India’s future diverged sharply. Understanding their interactions helps us appreciate the ongoing struggle for social justice and the enduring debate over the soul of India.

What were the main criticisms Ambedkar had about Savarkar’s ideas?

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s critiques of V.D. Savarkar were sharp, deeply rooted in their contrasting visions for India, and focused on several key areas:

1. Incomplete Approach to Caste Abolition

- Ambedkar believed Savarkar’s efforts against untouchability were limited because Savarkar still defended the concept of chaturvarna (the four-fold varna system), even if he claimed it should be based on merit rather than birth. Ambedkar saw this as “needless and mischievous jargon” and insisted that true social reform required the complete dismantling of the caste system, not just superficial reforms3.

- He criticized Savarkar’s initiatives, like the Patit Pavan temples, arguing they would only reinforce the idea of “temples of Untouchables” rather than achieving genuine equality.

2. Reliance on Hindu Scriptures

- Ambedkar argued that Savarkar and the Hindu Mahasabha failed to challenge the authority of Hindu scriptures, which he saw as the root of caste discrimination. Ambedkar insisted that social issues should be decided by the principles of social science, not by religious texts, and was disappointed that Savarkar did not go far enough in this direction.

3. Pan-Hindu Unity vs. Genuine Inclusion

- Savarkar’s idea of pan-Hindu unity was, for Ambedkar, more about keeping the numbers of Hindus high and preventing conversions, rather than a sincere effort to uplift the oppressed. Ambedkar accused the Hindu Mahasabha of lacking genuine concern for the “untouchables,” seeing their anti-untouchability stance as a “smokescreen”3.

4. Exclusive and Divisive Nationalism

- Ambedkar strongly opposed Savarkar’s vision of India as a Hindu Rashtra (Hindu nation), warning it would be “the greatest calamity for this country.” He saw Savarkar’s Hindutva as dangerously exclusive and divisive, undermining the inclusive, pluralistic fabric of Indian society.

- Ambedkar critiqued Savarkar’s two-nation theory, which claimed Hindus and Muslims were fundamentally separate. Ambedkar believed this perspective would create instability and conflict, rather than unity.

5. Contradictory Logic on National Identity

- Ambedkar called out Savarkar’s inconsistency: if Savarkar admitted Muslims were a separate nation with rights to cultural autonomy, how could he oppose their demand for a separate homeland while insisting on a Hindu homeland for Hindus? Ambedkar found this logic “illogical, inconsistent, and even dangerous” for India’s future.

6. Rejection of Hinduism

- Ultimately, Ambedkar’s most profound criticism was his rejection of Hinduism itself as irredeemably tied to caste and inequality, a stance that directly contradicted Savarkar’s efforts to reform Hinduism from within. Ambedkar’s mass conversion to Buddhism was a clear repudiation of the Hindu social order that Savarkar sought to preserve, even in reformed form.

In summary:

Ambedkar respected Savarkar’s activism against untouchability but condemned the limitations and contradictions of his approach. He found Savarkar’s reforms insufficient, his nationalism divisive, and his reliance on Hindu frameworks fundamentally flawed. Ambedkar’s vision was for a radically inclusive and egalitarian India, while Savarkar’s ideas, in Ambedkar’s eyes, risked perpetuating exclusion and conflict

What specific aspects of Savarkar’s Hindutva did Ambedkar find most dangerous

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s critique of Savarkar’s Hindutva was incisive and far-reaching. He saw several specific aspects of Savarkar’s ideology as deeply dangerous for India’s future:

1. Hindu Rashtra and Majoritarianism

- Ambedkar warned that Savarkar’s vision of a Hindu Rashtra (Hindu nation) would lead to the political domination of Hindus over minorities, especially Muslims. He argued that this would create a system where religious minorities would be forced to live under the authority and hegemony of the Hindu majority, undermining the very idea of equality and justice5.

- He famously stated, “If Hindu Raj does become a fact, it will, no doubt, be the greatest calamity for this country,” highlighting his fear that a Hindu-dominated state would threaten India’s safety, security, and pluralistic fabric5.

2. The Two-Nation Theory and Communal Division

- Ambedkar was critical of Savarkar’s endorsement of the two-nation theory, which posited that Hindus and Muslims were fundamentally separate nations. While Savarkar did not support partition, he advocated for Hindu hegemony over Muslims within a united India, which Ambedkar saw as a recipe for perpetual conflict and instability.

- Ambedkar argued that emphasizing differences rather than commonalities between communities would only deepen communal antagonism and make peaceful coexistence impossible.

3. Exclusionary Definition of Nationhood

- Savarkar’s definition of who belonged to the Hindu nation was based on whether one considered India their matrubhoomi (motherland) and punyabhoomi (holy land). This definition excluded Muslims, Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians, as their holy lands lay outside India. Ambedkar found this exclusionary and incompatible with the inclusive, secular vision he championed.

- Ambedkar saw this as “othering” religious minorities and denying them full belonging in the Indian nation.

4. Inadequate Social Reform and Retention of Caste Hierarchy

- While Savarkar spoke against untouchability and caste discrimination, he continued to defend the concept of chaturvarna (the four-fold varna system), albeit on the basis of merit. Ambedkar argued that this did not go far enough to dismantle caste hierarchies and would perpetuate social divisions under the guise of unity6.

- Ambedkar viewed such reform as superficial and “masquerading” as genuine change, insisting that true equality required the complete abolition of caste, not its rebranding6.

5. Incompatibility with Democratic Values

- Ambedkar believed that the rigid, hierarchical structure of Hinduism, as defended by Hindutva, was fundamentally at odds with the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity essential for a modern democracy.

- He saw Hindutva’s emphasis on religious identity and hierarchy as a direct threat to the constitutional values he enshrined in India’s legal and social framework.

In summary:

Ambedkar found Savarkar’s Hindutva dangerous because it promoted majoritarian rule, deepened communal divides, excluded minorities from the national community, failed to abolish caste, and clashed with the ideals of democracy and equality. He believed these aspects would not only endanger India’s unity and stability but also betray the promise of justice and inclusion at the heart of the freedom struggle

How did Ambedkar’s warnings influence the political landscape of India?

Ambedkar’s warnings profoundly shaped India’s political landscape by embedding key safeguards and values in the country’s democratic framework. He cautioned that:

- Internal divisions and placing creed above country could threaten independence again. Ambedkar’s fear that prioritizing caste, religion, or party over national unity might lead to a loss of freedom has kept the dangers of communalism and sectarian politics at the forefront of public debate. This has made secularism and national integration central themes in Indian politics.

- Democracy must go beyond elections to ensure social justice. Ambedkar insisted that political democracy would not survive unless it was rooted in social democracy-liberty, equality, and fraternity. His emphasis on bridging social and economic inequalities influenced the adoption of affirmative action policies and remains a touchstone for social justice movements.

- Hero-worship and unchecked power are threats to democracy. Ambedkar warned against “political bhakti” (blind devotion to leaders), arguing it could lead to dictatorship. This warning is often invoked in discussions about the concentration of power and the importance of holding leaders accountable, reinforcing the need for strong institutions and vigilant citizenship.

As a result, Ambedkar’s insights continue to guide debates on secularism, minority rights, social justice, and the dangers of authoritarianism, shaping both policy and public consciousness in India

Conclusion

In conclusion, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s critical engagement with Savarkar’s ideology left a profound mark on India’s political and social landscape. Ambedkar’s warnings against Hindutva’s exclusionary nationalism and superficial social reforms emphasized the need for true equality, secularism, and justice. His vision shaped the Indian Constitution, ensuring protections for minorities and the marginalized, and continues to inspire debates on democracy and social harmony. By challenging Savarkar’s ideas, Ambedkar championed an inclusive India where liberty, equality, and fraternity are paramount-values that remain essential for the nation’s unity and progress in the face of ongoing ideological challenges.